Annemarie Davidson: The Radiant Heart of California’s Mid-Century Enamel Movement

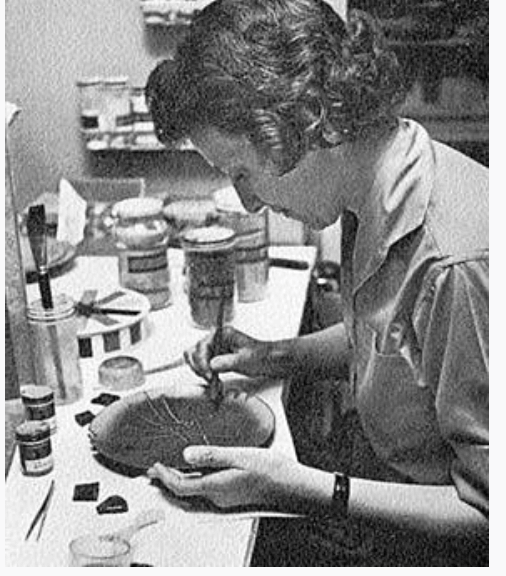

There are artists whose work feels alive—glimmering, shifting, catching light in a way that suggests something almost alchemical. Annemarie Davidson (1920–2012) was one of those artists. A pivotal figure in the American studio enamel movement during the 1950s and ’60s, Davidson helped transform vitreous enamel from a humble craft lineage into a distinctly modern art form. Her work sits at the crossroads of design, color theory, abstraction, and the joyful California sensibility that animated so much of postwar art.

Today, Davidson’s plates, bowls, and catch-alls are prized not only for their beauty and rarity but also for the way they capture a specific, electrifying moment in American design—when art leapt off the gallery wall and landed on coffee tables, sideboards, and dining spaces across the country.

A California Movement, and a Woman at Its Center

While enameling had deep historical roots in Europe and Asia, the studio enamel revolution in mid-century America germinated on the West Coast. Davidson was part of an unusually strong cluster of California enamelists—including Curtis Tann, Doris Hall, Arthur and Kay Gerber, and Mary Sharp—to name only a few. This small but influential network exchanged ideas, shared kiln knowledge, and pushed boundaries in form and technique.

Few outside the collector world know that Davidson’s early experimentation was encouraged in part by her husband, David Davidson, who built much of her equipment. David was an engineer by training, and he customized kilns, tools, and firing mechanisms that gave Annemarie an unusual degree of control over temperature fluctuations—a critical variable when you’re working with powdered glass that melts in seconds at nearly 1500°F. Their partnership was one of quiet but powerful symbiosis: her artistry paired with his engineering at a moment when studio craft was gaining national momentum.

Color as Language: Davidson’s Signature Voice

Davidson’s work is instantly recognizable. Rich jewel tones, luminous whites, and smoky ghostlines dance across her surfaces with controlled spontaneity. She developed—and guarded—her own enamel formulations, mixing commercial frit with custom blends to build depth and movement.

A few rare, insider details that collectors love:

1. Her “Ghostline” Technique Was a Happy Accident.

The ethereal white, gold, and green veining seen in her famous Ghostline series resulted from Davidson experimenting with under-fired layers. Instead of correcting the “imperfection,” she leaned into it, perfecting a method that produced soft, drifting halos—something no other enamellist executed with her finesse.

2. She Used Hand-Cut Copper Forms.

Rather than buying pre-cut blanks, Davidson often sawed her own copper shapes. This gave her greater control over edge integrity—important because enamel flows toward edges during firing.

3. Her Palettes Were Influenced by Los Angeles Light.

She spoke in interviews about the brilliance of California skies and how the clarity of the light influenced her preference for saturated turquoise, emerald, and midnight blues. Her work is often called “jewelry for the home”—a phrase attributed to a Pasadena gallerist who represented her in the late ’50s.

A Modernist Philosophy: Beauty for Everyday Life

Mid-century modern designers sought to collapse the divide between art and living. It was a belief shared by architects, furniture designers, ceramicists—and certainly enamelists.

Davidson’s plates, bowls, and trays were functional objects, yet visually arresting. She understood that a home could hold art in its most accessible, tactile forms. That approach placed her squarely in the same philosophical lineage as contemporaries like Edith Heath, Eva Zeisel, and the Natzlers—artists who infused everyday objects with sculptural presence.

This ethos is part of why Davidson’s work resonates so deeply today. A single plate on a credenza becomes a punctuation mark. A catch-all on an entry table becomes a story. Her pieces bring color, clarity, and quiet drama to any modern interior.

A Legacy of Luster and Innovation

Though she produced work for only a few decades, Davidson’s output remains relatively small—and therefore highly sought after. Collectors prize:

-

Her early 1950s work, often marked by dense, saturated hues

-

Her playful abstract compositions, referencing modernist painters

-

Her “Ghostline” plates, which are particularly rare in white-dominant palettes

-

Unusual forms, like large platters and deep bowls

-

Pieces with intact original labels, which establish provenance

As the mid-century revival has brought fresh appreciation to American studio craft, Davidson’s works have moved from niche collector circles into broader recognition. Museums and design scholars now position her centrally in the lineage of West Coast craft—alongside the great ceramics and metalwork studios of the era.

The Piece Today: A Radiant Artifact of Mid-Century Art

To acquire an Annemarie Davidson enamel plate is to hold a moment in American design history. These aren’t simply decorative objects—each is a small, glowing universe, suspended in molten glass and cooled into permanence.

Whether displayed on a Danish teak credenza, hung as a wall grouping, or set as a functional catch-all, a Davidson piece carries the unmistakable signature of California modernism: expressive, optimistic, and alive with color.

Add a rare and radiant piece of Mid-Century Modern art to your collection with a vintage enamel plate by Annemarie Davidson. Her work embodies the adventurous spirit of the 1950s and ’60s studio enamel movement—and continues to captivate collectors of mid-century enamelware, ceramics, and decorative arts.